Why 19.20.21. is important

May 10, 2009

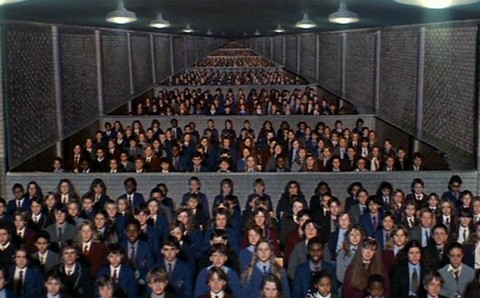

Richard Saul Wurman, prolific explainer and the creator of the TED conference, is back with a 5-year project called 19.20.21 to try and work out what makes urban environments tick. This is long overdue: over half the world’s population lives in cities, rising to 2/3 by 2050. By analysing 19 supercities with more than 20 million inhabitants, the project:

“will lead to a common means electronically, in print and real time, to comparatively describe the demographics , economies, health data and environmental data as it relates to the urban world.” (from 192021.org)

The powerful idea at the heart of this is that whereas the world used to be thought of as power struggles between countries, it is now “A Globe of Cities”:

“today, people think of the world as a network of cities – not a network of countries. We visit London, Paris or Rio de Janeiro, rather than England, France or Brazil. The world is now linked through mass channels of communication and transportation, managed by a patchwork of public and private interests.”

So what?

Cities grow organically and are the product of their host cultures, so it is no surprise that there is variation – in sanitation, transport, health, education, quality of life, crime etc… But how do you describe these differences? The words “crime”, “quality of life”, “public transport” may have literal translations in the languages of the world, but subtle variations in meaning are too much for a simple dictionary entry.

To understand these factors you need to have lived in both cities long enough to have experienced the right things. Worse, even people who have been fully assimilated in several cities would mostly have experienced them in a deeply personal way. If you spent your primary school years in London, secondary school in New York and university in Mumbai, could you really comment on their respective educational systems?

And even if you could explain the differences on a completely objective level, you’d still have to consider the perspective of the other culture. The exact same meal, maths lesson or knee operation might be seen as fantastic, adequate or deeply disappointing depending on expectations.

That’s why it’s so hard to answer the question asked by someone from a different city or country: “What it’s like where you’re from?”

19.20.21 = a common yardstick

Getting to the point where applicable lessons can be drawn from the world’s largest cities may take longer than 5-years, but the findings should be fascinating. Hopefully, the outcome will be a set of concrete design patterns which city planners can use to improve the lives of their citizens while reducing the environmental burden of urbanisation. These must do two things. 1) create an objective way to measure the success of a city’s elements, 2) make it possible to transfer these elements elsewhere.

Finding a common scoring system can kick start progress: take the introduction of the Apgar scoring of a newborn’s health, which slashed the mortality rate of babies in childbirth:

The Apgar score, as it became known universally, allowed nurses to rate the condition of babies at birth on a scale from zero to ten. An infant got two points if it was pink all over, two for crying, two for taking good, vigorous breaths, two for moving all four limbs, and two if its heart rate was over a hundred. Ten points meant a child born in perfect condition. Four points or less meant a blue, limp baby.

The score was published in 1953, and it transformed child delivery. It turned an intangible and impressionistic clinical concept—the condition of a newly born baby—into a number that people could collect and compare. Using it required observation and documentation of the true condition of every baby. Moreover, even if only because doctors are competitive, it drove them to want to produce better scores—and therefore better outcomes—for the newborns they delivered.

Around the world, virtually every child born in a hospital had an Apgar score recorded at one minute after birth and at five minutes after birth. It quickly became clear that a baby with a terrible Apgar score at one minute could often be resuscitated—with measures like oxygen and warming—to an excellent score at five minutes. Spinal and then epidural anesthesia were found to produce babies with better scores than general anesthesia. Neonatal intensive-care units sprang into existence. Prenatal ultrasound came into use to detect problems for deliveries in advance. Fetal heart monitors became standard. Over the years, hundreds of adjustments in care were made, resulting in what’s sometimes called “the obstetrics package.” And that package has produced dramatic results. In the United States today, a full-term baby dies in just one out of five hundred childbirths, and a mother dies in one in ten thousand. If the statistics of 1940 had persisted, fifteen thousand mothers would have died last year (instead of fewer than five hundred)—and a hundred and twenty thousand newborns (instead of one-sixth that number). (Atul Gawande in the New Yorker – also a story in his incredible book, Better)

Without a common yardstick, how can you know who has gone the farthest?

Or what about the impact on trade and industrialisation of common standards for railway gauges, shipping containers or even the metric system itself. In The Box, former finance economics editor for The Economist Marc Levinson explains how “an iconoclastic entrepreneur, Malcom McLean, turned containerization from an impractical idea into a massive industry that slashed the cost of transporting goods around the world and made the boom in global trade possible.” From the first chapter:

Some scholars have argued that reductions in transport costs are at best marginal improvements that have had negligible effects on trade flows. This book disputes that view. In the decade after the container first came into international use, in 1966, the volume of international trade in manufactured goods grew more than twice as fast as the volume of global manufacturing production, and two and a half times as fast as global economic output. Something was accelerating the growth of trade even though the economic expansion that normall stimulates trade was weak. Something was driving a vast increase in internationl commerce in manufactured goods even though oil shocks were making the world economy sluggish. While attributing the vast changes in the world economy to a single cause would be foolhardy, we should not dismiss out of hand the possibility that the extremely sharp drop in freight costs played a major role in increasing the integration o fthe global economy.

What are the equivalent costs of interaction between cities? What stops cities sharing more ideas on how to make urban environments fit both for people and for the planet?

I hope that this project will help identify the ideas which have worked best, and somehow explain them clearly enough that cities of any culture will be able to apply them. As many people as live in the entire planet today will live in cities in 2050. That’s why 19.20.21 matters, and I hope it succeeds.

Finguistics

January 22, 2009

For those of you who were interested in the game I mentioned in my last post, here is some more information from a couple of the developers who worked on it: Steven Robbins and Marc Gravell, which it turns out is called Finguistics. Guys, I really enjoyed the app you created and hope you get a chance to keep making more great stuff for the Surface.

Here’s an interesting quote from Marc about the genesis of this game:

“The aim was to demonstrate how RM could use Microsoft’s product to deliver a solution “of defensible pedagogic value” (direct quote), as part of the next generation of collaborative learning systems. Now I should stress that this was a prototype (not a product) – we were mainly trying to get people thinking about such tools in the education context, so we built an education game for spelling, languages and maths.”

More thoughts on BETT coming soon.

Interesting titbits from BETT 2009 (pt.1)

January 18, 2009

I managed to make it down to BETT on Saturday, and found that yet again, the golden rule of conferences continued to apply: the bigger your stand, the less likely you are to be cutting edge. Here are a few of the things that caught my attention:

Microsoft Surface

Okay, so I’ve just broken my golden rule, but getting to finally play on the Surface was genuinely cool (I promise not to break it again). The technology has been covered absolutely everywhere so I won’t go over it again (not seen it? this is cheesy but gives a good idea); what was interesting was to see some examples of it helping kids get more engaged with learning.

The kids above are playing a spelling game. Each of those little round tokens scattered on the table has a letter on it, and the aim is to press them in the right order to spell the word in the picture. The trick is that you have to press and *hold* them, so to do it before the time runs out you need a few more pairs of hands than just your own.

Why this matters? It was really fun, and quickly got everyone talking to each other. In this particular example, you have the engagement of a well designed game with the quality control that a computer system can bring, highlighting just how useful these table sized displays may become.

Apart from that, there was 3D virtual heart which you could fly around in, a drawing program where you could smear virtual paste around, and of course the usual table sized google maps (the kids absolutely loved that one, see picture)

This makes me really look forward to the rise of tabletop computing (and bartop, of course…).

Guardian news tools

Also interesting were a pair of projects by the Guardian, a major UK national newspaper, to get pre-teen children engaged in the news whilst at the same time teaching them valuable critical reading and writing skills.

The first project, LearnNewsDesk, was a large database of simplified news articles arranged into easily digestible chunks under each school subject area, with exercises and a glossary attached to each story. Kids can also upload podcasts and articles with their own takes on the news. New articles are added daily so the site is a good approximation of the real news.

Why this matters? It’s a good reminder that to be useful and remembered, information must be aware of its context. If you know that context you can add all kinds of metadata as a hook to help that information stick in the mind. In this case, the system provides a great sandbox which teachers can use to help young kids understand some important issues.

Project number two, Newsmaker was the flipside of the news desk, giving children a very simple collaborative, web based tool to create their own paper (see the solitary picture below). At the heart of it is a fixed template into which kids can put their own articles and picture.

One kid gets to be the editor whilst the others take on the roles of journalists and picture editors, with simple word processing and picture editing tools to insert their work. This is cool as it 1) provides a very simple platform for collaboration and 2) lets groups of pupils easily create a professional looking paper.

Why this matters? Easy. Somewhere along the way of trying to teach desktop publishing to ten year olds, schools have forgotten that just learning to lay something out with Microsoft Office is not enough – you need to have something to say with it too.

Peter Molyneux, maker of legendary and beautiful games, once said about hiring 3D artists (and I paraphrase as I can’t find the actual quote):

“It’s easier to teach a great artist to use a 3D modelling tool than to teach an expert in 3D Studio Max or Maya to be a great artist”

Tools like these which do one thing very well are a great way to get straight to the meat of what you are trying to do. Would you rather spend a lesson bogged down in the technicalities of Microsoft Publisher or actually publishing something?

Autology

Autology is a natural language search tool which does three rather interesting things.

- “Push” search. It watches what you are typing in Word or equivalent and can suggest relevant information. This is apparently already being used by MI5, the FBI, BBC, Reuters, Merrill Lynch, the Deutsche Bundesbank and IBM, and is yet another step towards computers seamlessly integrating with our processes. Instead of having to go to Google, Google comes to you.

- Vertical search. It indexes hundreds of high quality secondary school textbooks to increase the relevance of the results. Search focused on particular verticals is clearly going to be an interesting area if generalised search engines reach an upper limit to their accuracy

- Search folders. With this feature, a teacher or student can create a themed folder which gets automatically loaded with documents relevant to a particular search query. This is yet another example of dynamically structuring information to be most useful. If you’ve ever used a smart playlist in iTunes, you’ll know how handy this is, and it’s becoming increasingly important as information multiplies.

Why this matters? I can’t really comment on the theoretically improved quality of natural language vs keywords as I din’t have long enough to test it, but the push search is fascinating nevertheless. In the words of David Black of Autology:

“It is pattern recognition technology which is able to push relevant information to a user. There is no need to go and search for it. It can be pushed to you conceptually, matched to what you are writing about.

“It is like a student sitting in a library and as they are writing their essay somebody keeps coming up to them saying ‘you are writing about this, have you seen this?'”They are not having to go and get it. It’s as near as you are going to get to artificial intelligence.”

From the Birmingham Post

Computers have gone from filling a room to pocket sized, but still require us to play by their rules to get the most out of them. The next step is technology which knows what you need and discreetly sends it your way. Autology may be another tiny leap in this direction.

More highlights coming soon…

What caught your attention at BETT 2009?

Future of online learning (part 1)

January 14, 2009

In my last post I mentioned a fascinating essay by Stephen Downes: “The Future of Online Learning: Ten Years On”. In it, he revisits and updates his 1998 predictions about the future of education, most of which are apply heavily to business, which is already an environment where people have to learn at different paces. Here are five of the most interesting ideas from this long and thoughtful piece.

1. One task to rule them, and in the mashup bind them

“In 1998 I wrote that computer programs of the future will be function based, that they will address specific needs, launching and manipulating task based applications on an as needed basis. For example, I said, the student of the future will not start up an operating system, internet browser, word processor and email program in order to start work on a course. The student will start up the course, which in turn will start up these applications on its own.”

This paragraph is related to one of the big changes caused by the move towards a world where we perform complex tasks using an array of interconnected web applications, each with simpler functionality and hosted on an array of increasingly smart devices, each serving a more specific purpose and connected to each other via the Cloud. UNIX junkies with their tiny command line applications will be overjoyed. Developers of wonderful, hulking, multi-purpose applications (Microsoft and Office, Adobe and Creative Suite, Autodesk and AutoCAD) will find their most casual users chipped away.

The big challenge for designers of these tools is twofold: 1) their applications need to be open, and interoperate properly and, 2) the user experience will somehow need to be consistent enough not to confuse people.

Resources like http://www.programmableweb.com/ and organisations like http://www.dataportability.org/ are helping the industry to make headway on the first point. Thanks largely to Google Maps, the word mashup is now commonplace, and tools like Yahoo Pipes, Microsoft Popfly, JackBe, Dapper, Kapow, IBM’s QEDWiki, Proto, BEA AquaLogic and RSSBus.” (more here). This matrix is also pretty cool.

Number two is tougher, as there is more of a grey area between it working and not than when grabbing data from another service. However, it is crucial for designers to keep an eye on the development of standards in interaction design. For the web, frameworks like YUI which allow standard controls to proliferate are useful, although they must still be carefully used. Physical devices are an entirely different issue, and can turn an accepted way of interacting on its head (e.g. iPhone and touch and the Wii with motion sensing).

The main opportunity: get to know your customer and you will be able to meet their specific need better, faster and more cheaply than ever before.

2. Many screens – a.k.a. letting information come to us

“In 1998 I wrote that ‘The PAD will become the dominant tool for online education, combining the function of book, notebook and pen.” The PAD, I said, would be “a lightweight notebook computer with touch screen functions and high speed wireless internet access.” I also said it would cost around three hundred dollars…”

“With slim, lightweight technology, truly useful and portable PADs will be widely available within the next ten years. We have already seen significant improvements in screen technology, including slim touch-sensitive screens. Wireless access and cloud computing make bulky storage devices unnecessary; what local memory is needed will be more than adequately managed using tiny flash memory chips. Improvements in battery life and solar power will mean that these low-wattage portable computers will run for days. They will, as I suggested before, come in all shapes and sizes, from a slim pocket version (much like the iPod touch) to a notepad version..”

“The same technology that makes PAD technology possible will continue to proper improvements in large screen displays (devices I nicknamed WADs (Wide area Displays) ten years ago).

“In the future, it will be common to see these large-area displays hanging on living room and classroom walls. Instead of being the size of small windows, they will be the size of large blackboards. They will be touch sensitive (or if not, connected to a pointer tracking system device similar to the ones being cobbled together for less than $50 by Wii enthusiasts (Lee, 2007)) or included with any of a number of children’s educational webcam games today (such as Camgoo, among many others).”

For too long we have bent over backwards for computers, limited to a (relatively) small screen and a computer taking pride of place on our desk. In the future, the opposite will be true. We are surrounded by information. In the future, we will use an array of different devices to access it – from iPhone style handhelds for simpler tasks to desk and wall sized interactive touchscreens for the bigger ones:

“…imagine that any environment that contains a flat surface can become a teaching environment, one where your friends’ faces (or your parents’ or your teachers’) can appear life-size on any old wall or on a table surface as you converse with them from the next room or around the world. We have already seen how the availability of mobile telephones has transformed society in less than a generation. (New Media Consortium, 2008) Having much more powerful, much more expressive, communications technology available everywhere will have a similar impact.”

3. If it ain’t fun, forget it

“A great deal has been written in the last few years about educational games or, as they are sometimes called, ‘serious games’. (Eck, 2006) In 1998 I wrote that “educational software of the future will include every feature present in video games today, and more.” Though this hasn’t proven to be strictly true, it is largely true, and probably no more true than in the domain of games and simulations.”

“In 1998, I wrote the following: “To give a student an idea of what the battle of Waterloo was like, for example, it is best to place the student actually in the battle, hearing Napoleon’s orders as they become increasingly desperate, feeling the recoil of one’s own musket, or slogging through the mud looking for a gap in the British cannons.” (Downes, The Future of Online Learning, 1998) Today we can say that the creation of such simulations will not be simply the domain of large production houses, but will rather be more and more the result of massive collections of small contributions from individual players. And that the creation of content – any content – needs to take this phenomenon into account, or be seen as abstract and sterile.“

Giving people a chance to experience a situation they are learning about is an unusually good way of making sure they understand it. The humain brain is playful. As such, give it a complex environment to experience and you can guarantee that it will start pushing, pulling, prodding and generally attempting to find the way it works – trying to work out the rules.

Imagine trying to teach music by showing someone only the score to Mozart’s Requiem, or art appreciation by describing one of Turner’s sunsets. Ultimately, our subconscious minds are much more attentive than our conscious, which is why we get so much more depth from an experience than from a description.

4. Personalised learning, group evaluation

Another big idea is that of personalised learning environments. Instead of having students chug through a defined syllabus with standardised tests to mark the pace, the educational institution’s responsibility will be to connect them with projects, resources, games and members of the community around that domain. As they get more and more involved:

“…each person will have what may be thought of as a ‘profile’ of their own art, music and other media, which they have created themselves or with friends, along with records of their activities in various games and simulations (we see things like this already with applications like Launchcast) that take place both on and off line.”

What is really interesting is how all this will be tested:

“In the end, what will be evaluated is a complex portfolio of a student’s online activities. (Syverson & Slatin, 2006)These will include not only the results from games and other competitions with other people and with simulators, but also their creative work, their multimedia projects, their interactions with other people in ongoing or ad hoc projects, and the myriad details we consider when we consider whether or not a person is well educated.”

“Though there will continue to be ‘degrees’, these will be based on a mechanism of evaluation and recognition, rather than a lockstep marching through a prepared curriculum. And educational institutions will not have a monopoly on such evaluations (though the more prestigious ones will recognize the value of aggregating and assessing evaluations from other sources).”

“Earning a degree will, in such a world, resemble less a series of tests and hurdles, and will come to resemble more a process of making a name for oneself in a community. The recommendation of one person by another as a peer will, in the end, become the standard of educational value, not the grade or degree.”

5. Learning resources will annotate the world

“Online learning stiff suffers from the misperception that it is about having students sit in front of their computer screen for extended periods of time. As a consequence, the idea that online learning might foster independence of place has been missing in much of the discussion of the field. (…) That said, with the recent development of smaller and lighter wireless-enabled devices, we are approaching the era when online learning will also be seen as mobile learning. Students will be freed from the classroom, and freed from the stationary desktop computer. And as I said last time, true place independence will revolutionize education is a much deeper sense than has perhaps been anticipated.”

Much of what goes on about us has a history and a significance that we miss completely, whether it’s the context in which a piece of technology was developed or the story behind a piece of architecture. In a more concrete business context, it might be the profitability of a piece of machinery or the childcare problems of an employee you have a meeting with in 10 minutes, which are affecting his ability to concentrate.

Well designed learning resources have the potential to guide us through the physical world rather than pulling us away. Incidentally, that’s why walking tours of cities can be so interesting – you see these layers peeled back for you.

More to come.

Knowledge is a performance enhancing drug.

January 11, 2009

Next Wednesday is the start of BETT 2009, the world’s largest educational technology event. 30,000 teachers will be learning about the best, coolest new ways of helping others learn.

This is a very important event, and not just for teachers.

Of technology’s many contributions to human civilisation, education is where the rubber hits the road. Remote learning, electronic paper, digital note taking, individualised curricula, etc… are just the latest episodes in the series which started with the drawing of shapes in the sand.

What separates us from animals is how good we are at transferring knowhow to our children, which allows each generation’s knowledge to become a foundation for the next to build on. However, we are limited by the length of education – older brains may learn more slowly and, anyway, most of us start work at the end of our teens. In the UK, half of adults stopped at or before 16 (data, key). Slightly higher in the US.

As such, if we can make better use of those 12–15 years we can give a whole population a headstart. Humanity on steroids, if you will.

Knowledge is a performance enhancing drug.

As we get a better handle on the rules of learning we can make better tools to help apply them, and to teach our teachers to apply them. Furthermore, what goes in the classroom is only the beginning. The trend towards more decentralised, personalised learning is exactly what we need after formal education. These same tools and techniques may help us with our lifelong learning – whether training to better do our jobs, learn new skills or pursue our hobbies.

Every designer creating tools to help us visualise, manipulate, remember and use information needs to keep a close eye on teaching and education. With more and more people making a living in the information economy, each new tool is another potential mind hack.

The opportunities are huge.

“Acting white”

One caveat, which will be the subject of another blog post. We must never forget the context in which education takes place. For now, this anecdote is as illustrative as any:

“…black students who study hard are accused of “acting white” and are ostracised by their peers. Teachers have known this for years, at least anecdotally. [Roland] Fryer found a way to measure it. He looked at a large sample of public-school children who were asked to name their friends. To correct for kids exaggerating their own popularity, he counted a friendship as real only if both parties named each other. He found that for white pupils, the higher their grades, the more popular they were. But blacks with good grades had fewer black friends than their mediocre peers. In other words, studiousness is stigmatised among black schoolchildren. It would be hard to imagine a more crippling cultural norm.”

It’s not just the black-white issues. Students of all backgrounds have different motivators to take into account.

Eight ideas

Here are some thought provoking resources and events on education:

- Go to the BETT TeachMeet, a pecha kucha style event from 6–9pm in Friday 16th. What is pecha kucha? 20 slides * 20 seconds = six minutes and 40 seconds on whatever, in this case exciting ways people have been using technology to teach.

- See what happened at BETT 2008. Podcasts. Summary video.

- Read about education in 2018. Stephen Downes wrote a paper called The Future of Online Learning which looked 10 years ahead from 1998. He was mostly right, and has now written a fascinating follow up available here. Most interestingly: we learn better by doing, so how can we use games to engage students with memorable simulations? As interestingly, learning may shift towards overlapping communities centered both around knowledgeable peers and trained teachers.

- Attend an unconference. Education2020: “If you want to attend an informal, congenial, stimulating event in an amazing location with brilliant and insightful people (including you, of course), then pop along to the Education2020 UNCONFERENCE wiki and get your name on the list. Not only will you be able to enjoy a great educational debate and discussion, you will also be travelling to one of the most beautiful places in Scotland.”

- Listen to some podcasts. EdTechRoundup: “conversations about using technology in education”

- More – 2020 and beyond. How about another point of view? In this paper, FutureLab looks at the impact of “personal devices, intelligent environments, computing infrastructure, security and interfaces”.

- Not enough? See 2025 and beyond. http://www.beyondcurrenthorizons.org.uk/

- Informal learning. VISION magazine issue 8, page 9.

More on BETT coming soon.